The UK’s electorate has spoken and there is to be a change of government in London. Among the many questions on our minds concerning next steps are sector-specific ones. New ministers now have to develop policies and plans for the management of the UK’s economy and major sectors of the economy. The automotive industry is well and truly in the mix when it comes to the new government’s industrial strategy. To make things even more interesting – or complex – it’s a sector that is in the throes of major transformative change led by advanced technologies.

There is the immense challenge of net-zero and the energy transition away from combustion engines to electric powertrains. On top of that, there is the small matter of promoting sustainability all along complex value chains that span the supply of raw materials such as steel, through all the tiers of parts manufacturing, to retail and aftermarkets – not forgetting the jobs that lay in vehicle manufacturing/assembly.

The industry’s UK automotive trade association, the SMMT, has some compelling stats on how important the sector still is to UK plc. Automotive-related manufacturing contributes £93 billion turnover and £22 billion value added to the UK economy, and typically invests around £4 billion each year in R&D. Many of these automotive manufacturing jobs are outside London and the South-East, with wages that are around 13% higher than the UK average. The sector accounts for 12% of total UK exports of goods with more than 140 countries importing UK produced vehicles, generating £115 billion of trade in total automotive imports and exports.

More than 25 manufacturers build in excess of 70 models of vehicle in the UK supported by 2,500 component providers and some of the world’s most skilled engineers.

Over 905,117 cars, 120,357 commercial vehicles and 1.62 million engines were built in the UK in 2023. It is estimated that there are more than 198,000 people employed in manufacturing and some 813,000 in total across the wider automotive industry across Britain. As economists well know, there is also the multiplier effect from all that economic activity. It’s an industry for policymakers to take notice of and handle with care.

Regarding the UK automotive sector, a look at both main parties’ (Conservatives and Labour) election manifestos was rather light on detail.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataICE timeline bans and ZEV mandate

One thing that did attract some attention was the Labour Party manifesto pledge to bring forward the ban on ICE-only car sales from the current 2035 to 2030 to boost net-zero aims. The previous government had initially gone for a 2030 hard-stop, but then decided to push it back five years to 2035. So it could be heading for 2030 again.

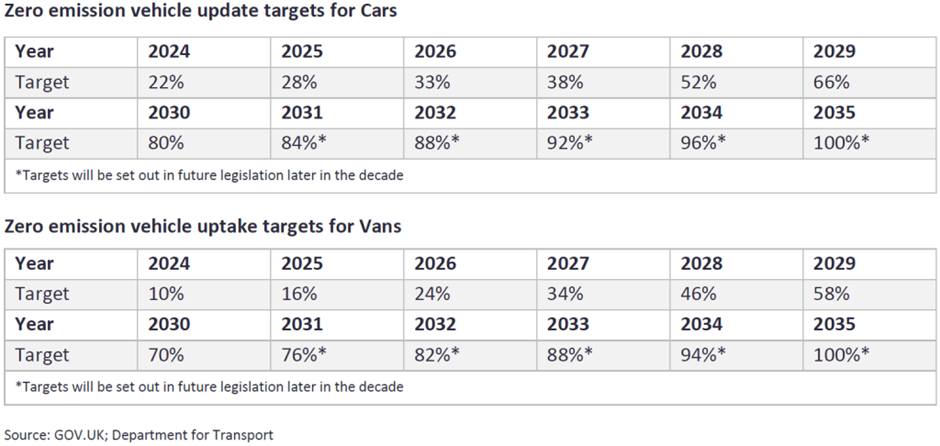

However, the last change from 2030 to 2035 appeared to be a little undermined by leaving the UK zero emission mandated share ladder (‘ZEV mandate’) in place. The below table sets out the details. Under the ZEV mandate, 80% of new cars and 70% of new vans sold in Great Britain must be zero emission by 2030. This percentage will increase to 100% by 2035. As it stands then, it’s already 80% by 2030.

It will be interesting to see how this year works out – but sluggish car EV sales are running well under the 22% 2024 target. It is clearly going to be missed by at least 3%, so it will be interesting to see how it works out with the fines for non-compliance (every car sold over the limit subject to an eye-watering £15,000 fine). There is also some considerable ‘devil in the detail’ with manufacturers able to compensate with fleet average CO2 performance, pool targets across brands and ‘bank and borrow’ ZEV sales between years. The whole thing was due to be reviewed in 2026, but a new government may want to consult the industry on its views much earlier.

To put the UK ZEV mandate and 2035/2030 ban question in perspective, many OEMs are working on strategies to massively electrify their European car market offerings by 2030 anyway. It is worth noting though, that the 2035 deadline for phase-out is in line with other major global economies such as France, Germany, Sweden and Canada. The 2035 timeline, it is argued, allows time for consumers to make the choice to switch to electric, and for the UK to better develop its EV battery charging infrastructure.

I would expect the incoming government to consult the industry, but the headline 2030 shift may go down well on net-zero grounds with its supporters and new Labour MPs at Westminster. In reality though, more attention in the industry will be focused on the workings of the ZEV mandate. The ZEV mandate is due to be reviewed in 2026, but a new government may want to consult the industry on its views much earlier – in the context of 2030 or 2035 for the ICE sales ban.

Addressing sluggish BEV uptake for private consumers

Which brings us to the more general issue of making it more attractive for vehicle users to switch to electric. The shift from ICEs to hybrids (good for CO2 fleet averages) and BEVs is a big ask on the demand-side as well as supply-side.

As many in the industry have pointed out, fleet sales are driving BEV numbers; private buyers are proving resistant to replacing ICE vehicles with BEVs for all sorts of reasons (purchase price; battery charging infrastructure; general uncertainties over the new tech). Are there tax incentives that can help?

The SMMT has called for fiscal incentives for the private consumer by way of a halving of VAT on BEVs for three years, claiming that would re-energise the market, putting an additional 300,000 private BEVs – rather than petrol or diesel cars – on the road over the next three years. This, it says, would help ensure that in 2035, half of all cars in use would be zero emission, cutting road transport CO2 emissions by 175 million tonnes between now and then.

It also says Vehicle Excise Duty (VED – an annual road tax levied on vehicles in use) plans should also be revised so zero emission vehicles (ZEVs) are classed as essential rather than ‘luxury’ vehicles, by amending the ‘expensive car’ supplement due to be applied from next April. In addition, it says public charge point use could be made fairer by reducing VAT from 20% to 5%, in line with home charging – a move that would support ZEV uptake and ‘send the right message to consumers’.

Anything to do with taxes is likely to attract a cautious approach from the new government, but it will be obvious that some levers may have to be pulled to get additional BEV sales on the path to net-zero. The ZEV mandate quickly becomes painful if there is significant buyer resistance to BEVs that cannot be overcome. There is also an issue with charging infrastructure provision and working with the energy sector on getting more public charge points. Calibrating supply and demand for BEVs at much higher volumes is obviously the major challenge.

An industrial and manufacturing strategy

This is a complex one, but it will be demanding attention because of the underlying importance of automotive manufacturing to the country’s economy. The UK’s auto industry sits in a somewhat precarious position on the edge of Europe and outside the EU trading bloc that comprises its biggest trading partner. There is a free trade deal between the UK and EU in place, but there are some uncomfortable questions on what happens to future trade arrangements and rather arcane areas such as Rules of Origin (in determining UK/EU mutually agreed local content levels for free movement of goods). It is made doubly uncomfortable because of the transition to electric vehicles and where batteries/cells are coming from when fitted to UK-made vehicles destined for shipment to the EU. Trade arrangements with other parts of the world also stand to be potentially impacted – due to the existence of EU free trade deals – by UK-EU rules on what constitutes local content on UK-made vehicles. Let’s not go down the rabbit hole of how country of origin may be measured for component systems at international borders.

Any industrial strategy will need to take account of prevailing (and forecast) trade flows in major components and finished vehicles. As supply chains flex for electrified vehicles, there is much at stake in terms of where future economic activity is located. Gigafactories for batteries are a high-profile element, but there is much to play for in terms of other BEV components systems. Talking to the major OEM actors (Tata Motors/JLR, Nissan, BMW/Mini…as well as industry bodies such as the SMMT and IMI) and getting a sense of their sourcing strategies and future needs should be a priority. There is also the engineering and development work – and the skills and resources needed for that – to consider, besides the nuts and bolts of what’s made where and understanding the nature of international supply chains.

Once that level of understanding is there, a credible strategy for the sector in the UK can take shape. It’s not only manufacturing of course, but also areas such as skills gaps for BEVs in future repair and maintenance. Attracting more investment for the sector in a highly competitive global landscape won’t be easy. Moreover, there’s a need for the UK’s globally competitive offering to be particularly relevant in the skills base and resources for R&D and associated advanced technologies such as AI and digital.

China tariffs on BEVs, EU relations

The EU has decided to impose provisional duties on Chinese BEV imports on the grounds that their low price points came with the benefit of anti-competitive subsidies. The competitive challenge presented by the Chinese OEMs is very real and manufacturers such as BYD and SAIC (MG) have targeted the UK market as well as EU ones. One difference between the UK and EU countries such as France and Germany is that the UK is less exposed in terms of European manufacturers making mass-segment cars – soon to be electric – here. In terms of future UK sales, cheap Chinese BEVs for sale in major market segments may be of more concern to Nissan than JLR, but the economic stakes are perhaps not as potentially high as they would appear in Wolfsburg or Paris.

Indeed, there is an opportunity for the UK to adopt a more ‘welcoming’ stance to the Chinese OEMs with no additional EU-style import tariffs. If the Chinese subsequently targeted the UK market though, that might be a real concern to some incumbent brands at the UK retail end.

So, there is potentially a question on whether the UK will follow the EU and add tariffs of its own, but the threat and potential protectionist response is less immediate in terms of the UK’s industrial base.

Looked at in another way, more low-cost BEVs – wherever they are from – are a way to get quicker progress in transport’s contribution to net-zero. Need a solution for low BEV take-up? Let the Chinese in big-time to the UK car market with their much cheaper small electric vehicles? Double-edged swords and all that. Of course, European OEMs may rise to the Chinese threat in BEVs with their own low price point BEVs, but they might not relish competing in Britain against entirely tariff-free Chinese products. Potential trade tensions wherever we turn.

Another big question perhaps lies in the mechanics of trade relations between the UK and the EU. The next government may well want to generally reduce friction on trade between the UK and EU; we can probably expect the mood music between London and Brussels to change in the direction of talking about greater cooperation. Local content and Rules of Origin applying to vehicles and parts shipped between the two territories are a headache that occasionally rears its head. That’s always going to be a potentially complex and politically sensitive matter, but both sides may well have an interest in putting in place better arrangements for cross-border trade of automotive industry products.

Finally, a point on the bigger picture. The incoming Labour Party made much of its commitment to higher economic growth (to make the big sums add up) in its election campaign. Attention in the automotive industry, like others, will inevitably be drawn in the coming years to the UK’s overall economic performance and the environment for growing their businesses, achieving higher product sales and being in a position to invest more. The sector details count for little unless the overall performance of the economy – the sum of the parts – is delivering.