When the UK’s Labour Party took power, the transition to electric vehicles was high on the agenda. Keir Starmer came into government on a raft of plans and promises around electric vehicles, and for good reason. Even though we are now less than six years away from the ban on new diesel and petrol vehicles in the UK, there is still a great deal of reluctance around electric vehicles from consumers.

In its Plans for the Automotive Sector, Labour itself acknowledged that “information asymmetry” has led to cynicism and anxiety around electric vehicles among consumers. 47% of drivers are concerned about battery durability, while 56% of drivers believe that the range loss from batteries is as much as three times worse than is the case.

To build confidence among consumers, Labour announced plans for an Electric Vehicle Confident labelling requirement for new electric vehicles to allow drivers to make informed decisions. It is an idea that mirrors the use of Monroney stickers in the United States. These require manufacturers to provide accurate information about the carbon footprint of a vehicle’s production and its usage relative to an ICE comparison, as well as the real-life range of the vehicle’s battery in different settings, and the battery’s expected lifespan.

A necessary health check

But while this addresses problems in the new vehicle market, most consumers can not afford to buy a vehicle brand new. The used car market represented 82% of all cars sold in the UK in 2021. This is exacerbated in the electric vehicle market segment, where the typical price point is even higher. A vehicle market led by electric vehicles will have to be a vehicle market led by second-hand electric vehicles, and that will not be possible without more government support. It comes back to consumer confidence, particularly around the battery health in used vehicles.

As Philip Nothard, Chair of the Vehicle Remarketing Association, points out, “Much of the feedback that we receive from our members about consumer resistance to EVs surrounds the possibility of battery failure. Many used car buyers have heard that batteries potentially cost tens of thousands of pounds to replace and tend to equate them with the kind of battery degradation that you might see in a smartphone or laptop, even though these lack the sophisticated battery management technology found in EVs that promotes longer life.”

This is not just an issue among drivers, but also buyers in the industry.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“While trade buyers might be better informed about battery design, they want to make sure that they are not buying a car with a faulty battery, so they are also looking for some form of testing that gives them the necessary information,” Nothard adds.

The Labour Party’s proposed solution is to implement a standardised battery health certification scheme for used vehicles. Labour has pointed to similar schemes already underway in countries such as Norway, potentially introducing a mandate that mirrors European Union proposals to require the fitting of battery state-of-health monitors to new electric vehicles.

It is a proposal that has received some positive feedback from the industry.

“Battery health certificates offer impartial, accurate information about the battery so that buyers and sellers can have confidence in what they are buying or selling,” says Alex Johns, partnership lead at Altelium, a firm that provides warranties, insurance and consultancy for businesses working with batteries. “This will also improve pricing accuracy.”

It is a solution that Nothard is sanguine about.

“For both sets of buyers, what a state of health check (SoH) provides is a high level of reassurance that the battery in the used car they are considering is in good condition, has been well looked after, and is not about to fail,” he says. “For consumers, it’s possible this could be linked to some kind of independent long-term battery warranty, even though most manufacturers provide eight years of cover.”

ClearWatt is a platform designed to provide comprehensive information, tools, and a community to support those who buy, sell or own electric vehicles.

Patrick Cresswell, co-founder and Managing Director of the company, also emphasises the importance of keeping drivers and dealers informed about the health of batteries in used electric vehicles.

“Providing confidence to consumers on the topic of battery health will have a material impact on the health of the second-hand BEV market,” he says. “Consumers need a real view on the health of the asset they are intending to buy as well as closely linked topic of realistic range performance and other key data points.”

Making the idea a reality

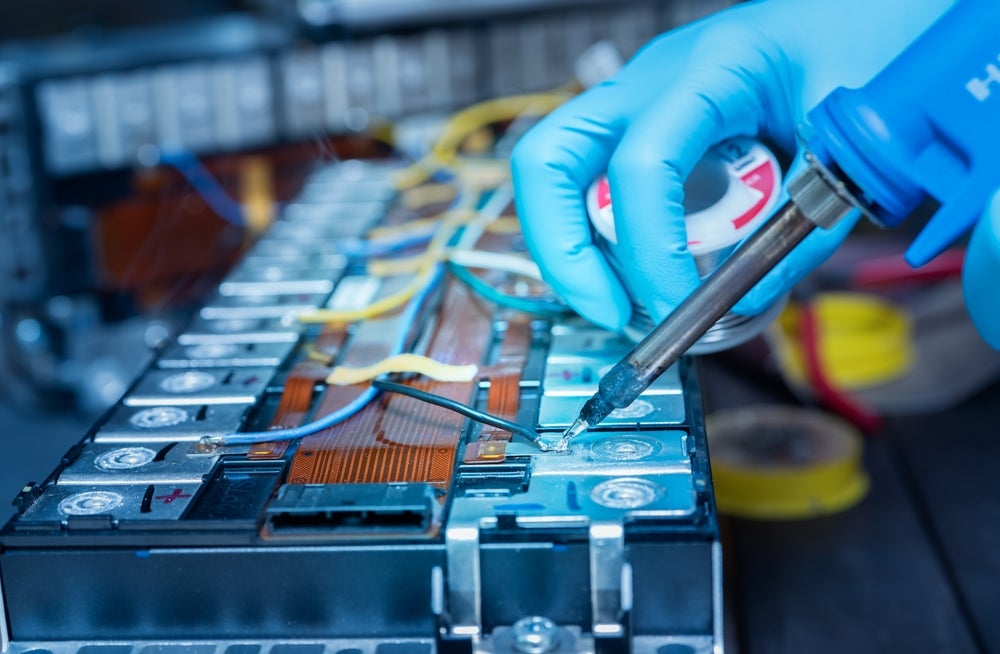

So while the use case for such a health certificate system might seem clear, the remaining question is whether such a system is feasible, and what it would take to implement that system.

“Each vehicle would have to be tested somewhere in the resales process, ideally as early as possible, with the results available to all parties,” Johns points out. “It helps if the certificate is prepared by an independent party which has no interest in the vehicle sale – this adds the credibility of having no vested interest in the sale; wishing to present the battery health either higher or lower.”

While the scheme is certainly possible from a technological standpoint, as Nothard points out, technology is only one of the factors that need to be taken into consideration in what this would look like in the UK.

“The technology certainly exists to implement a system of this type and really the question now is what direction the market takes? The new Labour administration looks to be committing to an SoH standard based on a United Nations technical standard, and there is a strong argument that some form of government-approved scheme would provide additional reassurance for buyers,” he says.

Northard also points out that the market is already offering its own solutions to EV battery confidence.

“There are already a number of credible suppliers in the market offering SoH checks and they could ultimately become part of, or sit alongside, the government programme,” Nothard says.

Indeed, ClearWatt is just one of the companies that is positioned to provide services in this area.

“At ClearWatt we have developed a system which can test and certify any EV and are already bringing this to market, with several EVs now being sold by retailers carrying our health certificates,” Cresswell tells us.

Cresswell also points to another key issue in the implementation of the Battery Health Certificate scheme. It will only attain its stated goals if both consumers and the industry at large are confident in what the certificates report.

“Ensuring that the test is completed at the right time during the resale process is key,” says Cresswell. “Dealers need to know what they’re buying before they purchase stock, which is why our system has been designed to be used at any point during the resale process – ideally at the disposal and remarketing stage, with the benefits of transparency cascading down to all future buyers and sellers.”

Of course, for the scheme to be implemented properly, other questions need to be answered, and as usual one of the first ones is “Who will pick up the bill?”

“A party needs to pay for it and therefore realise the added value it creates,” Johns says. “Not all parties in the Value Chain have worked out how to monetise the value in the Battery Health Certificate. Once a battery health test has been completed, it then needs to be shared with all interested parties.”

Learning by example

But whatever benefits and challenges a Health Certificate scheme might present, the truth is this is not an untested idea, and we can look to similar schemes to learn from their example.

“Most markets are approaching this in parallel. They have a variety of market structures, dynamics and stages of development, but the principles and technologies are largely the same,” Johns points out.

Nothard also looks to European examples that are leading the way.

“The Car Remarketing Association of Europe (CARA) has introduced its own standardised SoH test, which is being offered by a number of suppliers across several countries,” Nothard tells us. “It’s relatively early days for them but the market appears to have been very receptive.”

The other argument for a battery health certificate scheme is that, frankly, there are few other alternatives on the table. It is clear that a solution is needed which gives buyers the confidence to buy an electric car with an expensive battery.

“If the answer is not a battery SoH check, it’s difficult to envisage what it might be,” Nothard acknowledges.

But while it might be true that a health certificate system seems like the only option, the precise form that Health Certificate system takes is still open for debate, and there are several possibilities on the table.

“There are a number of different technologies and types of Certificates, but the concept that a battery needs to be tested and a certificate offered remains pretty much the same,” Johns says. “The reason it matters so much is because the battery degrades differently to a standard age and mileage profile, and is the most valuable part of an EV. Until these key factors change, Battery Health Certificates will remain very important.”

Even when a model for the battery health certificate has been established, Cresswell argues that it can only be one piece of the puzzle. The eventual solution, whatever form it may take, will involve a much wider network of information sources and data points.

“We believe battery health is one component of a much wider issue regarding a lack of information and data in the used EV market,” Cresswell says. “As such the three-page ClearWatt report issued on every tested car tackles all of the key areas in which a used EV is different to a used ICE vehicle – including range under different conditions, charging times and costs, the number of compatible public charge points, the impact of the way the specific car has been spec’d (such as the range impact of the choice and size of wheel) and many other data points. As the market moves firmly beyond early adopters, it’s critical that comprehensive information is provided so that consumers are supported through the process.”

Labour’s own election materials propose the Battery Health Certificate alongside measures to improve the accessibility of charge point data for businesses and consumers. They have also promised to lighten the burden on consumers, finding a replacement for the countless apps drivers currently rely on, and the questionable quality those apps offer.

The Labour Party has said it supports moves to make charge point data Open Access as part of an industrial strategy to use data for the public good. It has also said that it will set quality standards for the information charging apps provide.

The eventual certification scheme, whatever that scheme looks like, will be measured by how many people start purchasing EVs in its wake. So far, the evidence is on the side of such a scheme.

“There is emerging evidence to suggest that EVs with Battery Health Certificates both sell for a few per cent more and sell several days quicker than EVs without,” says Johns. “These benefits will make a considerable difference to EV adoption and offer a very high return on investment on the Battery Health Certificate.”

Cresswell also says that there is an urgent need to inspire greater confidence in consumers around battery health.

“There is a wealth of evidence highlighting the need for battery health confidence, including research from the Green Finance Institute, Auto Trader and others,” he says. “Dealers have reported to us that selling a car with a battery health report attached provides much-needed confidence which is one key component to optimising the whole resale process, in turn driving adoption.”

That confidence is going to be the foundation of the EV transition.

Could battery swapping replace EV charging?

Decline in battery prices set to accelerate global EV market growth: MCG report

Labour’s 2030 ICE ban may allow hybrid sales until 2035